Dairy is compared to other foods for cardiovascular (heart attack and stroke) risk.

When studies funded by industries suggest their products have neutral health effects or are even beneficial, one question you always have to ask is, “Compared to what?” Is cheese healthy? Compared to what? If you’re sitting down to make a sandwich, cheese is probably healthy—if you compare it to bologna, but what if you compare it to peanut butter? No way. That’s the point made by Walter Willet, former Chair of Nutrition at Harvard, as I discuss in my video Friday Favorites: Is Cheese Harmful or Healthy? Compared to What?

“To conclude that dairy foods are ‘neutral’…could be misleading, as many would interpret this to mean that increasing consumption of dairy foods would have no effects on cardiovascular disease or mortality. Lost is that the health effects of increasing or decreasing consumption of dairy foods could depend importantly on the specific foods that are substituted for dairy foods.”

Think about what you’d put on your salad. Cheese would be healthy compared to bacon, but not compared to nuts. “For example, consumption of nuts or plant protein has been inversely associated”—that is, protectively associated—“with risks of coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes; in contrast, intake of red meat has been positively associated with these outcomes. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the lack of association with dairy foods…puts these foods somewhere in the middle of a spectrum of healthfulness, but not an optimal source of energy or protein…More broadly, the available evidence supports policies that limit dairy production and encourages production of healthier sources of protein and fats.”

Willet wasn’t just speculating. His statements were based on three famous Harvard studies involving hundreds of thousands of men and women exceeding five million person-years of follow-up.

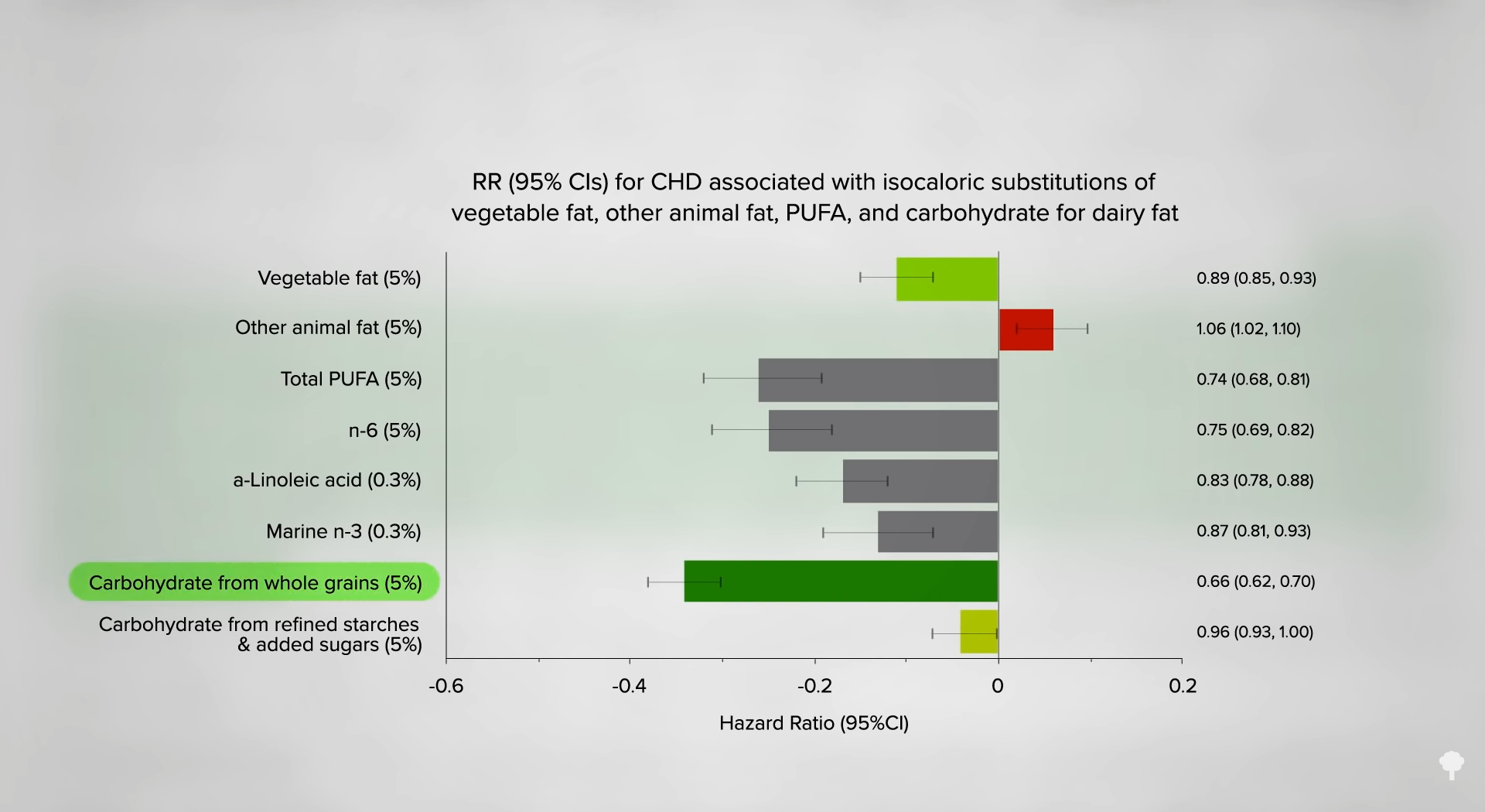

What was learned in the first large-scale prospective study to examine dairy fat intake compared to other types of fat in relation to heart attack and stroke risk? Replacing about 100 calories worth of fat from cheese with 100 calories worth of fat from peanut butter on a daily basis might reduce risk up to 24 percent, whereas substitution with other animal fats might make things worse. You can see a graph showing how it breaks down for heart disease at 2:07 in my video. Swapping dairy fat for vegetable oil would be associated with a decrease in disease risk, whereas swapping dairy for meat increases risk. Calories form dairy fat may be as bad as, or even worse than, straight sugar. The lowest risk would entail replacing dairy fat with a whole plant food, like whole grains.

Yes, “dairy products are also a major contributor to the saturated fat in the diet and have thus been targeted as one of the main dietary causes of cardiovascular disease (CVD),” the number one killer of men and women, but the dairy industry likes to argue that there are other components of dairy products, like fermentation by-products in cheese, that could counteract the effects of their saturated fat. This is all part of an explicit campaign by the dairy industry to “neutralize the negative image of milk fat among regulators and health professionals as related to heart disease.” If the Global Dairy Platform looks familiar to you, you may recall that it was one of the funders of the milk-and-dairy-is-neutral study, trotting out their dairy-fat-is-counteracted notion, to which the American Heart Association responded that “no information from controlled studies supports the hypothesis that fermentation adds beneficial nutrients to cheese that counteract the harmful effects of its saturated fat.”

We need to cut down on dairy, meat, coconut oil, and the like, no matter what their respective industries say. In fact, that’s the reason the American Heart Association felt it needed to release a special Presidential Advisory in 2017. It wanted to “set the record straight on why well-conducted scientific research overwhelmingly supports limiting saturated fat in the diet.”

Everything we eat has an opportunity cost. Every time we put something in our mouth, it’s a lost opportunity to eat something even healthier.